Dancingly Yours

Sad Case, Trois Gnossiennes, Whirling, Études

Details

In Brief

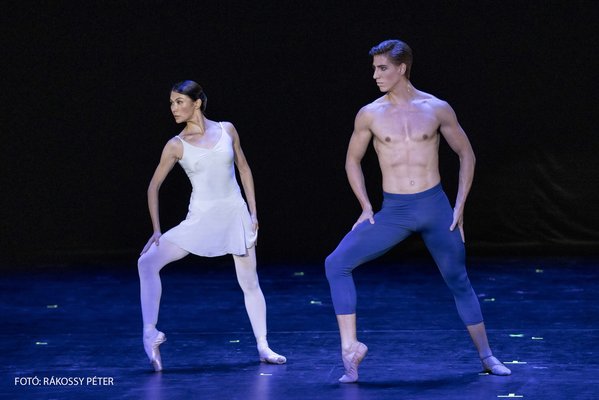

At its programme entitled Dancingly Yours, the ballet company of the Hungarian State Opera presents a selection of the most popular contemporary one-act works. The works by outstanding creators of the dance world, demanding breathtaking technique, portray the relationship and interdependence of men and women, offer a glimpse into an exciting yet unknown future, and depict finding your path on stage, where ballet itself also becomes a protagonist. With the combination of classical and contemporary, intimate and spectacular, melancholic and uplifting, the Hungarian National Ballet remains “Dancingly Yours”.

Parental guidance

Events

Premiere: Feb. 7, 1998

Sad Case

“Now in hindsight we realise that energy is everything. When we created Sad Case in 1998, so far in to Sol’s pregnancy, the hormones were jumping and emotions were high. It is these hormones of laughter, madness and the trepidation of the unknown ahead that are the umbilical chord of this work,” says the British Paul Lightfoot, thinking back to the origin of the ballet. He and his partner, the Spanish Sol León share credit for the performance’s choreography and set and costume designs. Up until 2020, León worked as artistic consultant and Lightfoot as artistic director for the Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT), where they were responsible for bringing about sixty creations, including Sad Case, which is undoubtedly one of the pillars of their work. In it, surprising movements set to Mexican mambo music reflect the ongoing search for the tension between the satirical and the serious. The OPERA had long planned the staging of this irresistible modern piece for Hungarian audiences – and by way of it, the art of the world-famous Lightfoot.

Trois Gnossiennes

Built around the magically beautiful music of Erik Satie, Hans van Manen’s Trois Gnossiennes draws a picture of a unique relationship. This double portrait painted with sensitive brushstrokes flashes with images of trust, submission and dominance, and relativity and interdependence. Masterfully alternating between lyrical and grotesque elements and weaving together memorable human traits, van Manen depicts monologues and dialogue, as well as symbolic moments of a relationship rich in intimate profundities. The bravura elevation of simple poses to the level of acrobatics and the enigmatic and fantastic play with a living body that goes limp make this short but dense work an unforgettable one.

Whirling

Whirling, a pas de deux by András Lukács, a former soloist with the Hungarian National Ballet is set to the second movement of Tirol Concerto by Philip Glass's, one of the greatest masters of repetitive music. The nearly fluid movement, the infinite harmony among the dancers and the unique style of choreography make the scene both quite exhausting and complicated. In 2010, the Hungarian National Ballet commissioned Lukács to create an expanded version for nine pairs. Tastefully and thrillingly combining elements based on classical techniques with modern devices, Lukács primarily creates plotless choreographies that are highly expressive. In Whirling, along with the music, the spiralling movements of the dancing superbly illustrate a vortex of water: the water into which the suicidal Virginia Woolf casts herself to music once again by Philip Glass in the film The Hours.

Études

Études is a one-act ballet which poses a great challenge to ballet companies because its subject is the technique of classical ballet itself: the school, the everyday training and the assessment of understanding and skill. Perhaps this is why the famous American dance critic Arlene Croce dubbed this work an “anti-ballet”. Because, in a ballet, the perfection of skill in dance is traditionally presented to the audience through the content, and the arduous everyday practise usually remains hidden from the viewers. The dancer’s everyday work takes place in the ballet studio, where the “vocabulary” of dance is formulated inside each dancer’s body, which will later become the base for the performance of choreographies on the stage. The audience sees only the outcome. Danish choreographer Harald Lander, however, decided to initiate the viewer by presenting on the stage how a ballet exercise is constructed, and how the pure beauty of classical movements and steps triumph over even the laws of physics. Since the rediscovery of Études in Budapest, it has represented a tremendous opportunity for the company’s soloists and provided enjoyable, spectacular entertainment for the audience.

Media

Reviews

Sad Case

"Two female and two male soloists bring a scintillating, pulsating energy to Latin American music on stage. The choreographer couple's extraordinary language of movement demands a high degree of physical flexibility: amazing writhing similar to rubber dolls."

Ira Werbowsky, Der neue Merker

Trois Gnossiennes

“The whole effect was spellbinding. The interest of the piece also comes from the fact that Satie’s achingly beautiful music strikes a chord with van Manen’s clarity of structure."

Jade Larine, Bachtrack

Études

“Both ballets are extreme compilations of vigorous ballet technique. Those ballets require virtuosity in bursts, often punctuating less onerous scènes d’action; these ballets require a lexicon of the toughest dance vocabulary, from start to finish….In particular, one must applaud the excellence of the ballet masters for the overall magnificence of the corps de ballet across both works.”

Graham Watts, Bachtrack

Ballet guide

Sad Case

Sad Case is far from being a sad story: on the contrary, it is rather cheerful, sometimes grotesque, ironic, special, irregular, and elusive. However, the greyness and enervation of downheartedness is definitely missing from it. Every moment of it is connected to life, to a real, down-to-Earth passion that becomes embodied flesh and blood. The piece was created in 1998 when Sol León was seven months pregnant with her daughter and was living the freest part of her life. This elemental joy of creation and saying yes to life seeped into the piece, entirely defining its genesis. When the creative process seemingly takes control of our own consciousness, talent, and experience is a special event for even the most inspired artists. In the interpretation of León and Lightfoot, Sad Case is just such a piece: it arrived in practically a couple of moments, naturally and without questions. Since then, the ballet has been performed in an adapted version.

The uniqueness of the movements stems from a mixture of the accuracy of the physical body and its motions and the unstoppable instinct that erupts from its depths. The exciting motions consisting of strong gestures are set to Mexican mambo music, providing both a satirical and a classical dance experience. In one of the movements, the human body becomes quite animal-like, only to return to its perfect form and then again to an animal-like gesture. The series of abstract scenes are connected to become a story by the viewer’s experience: the creator provides full freedom and a beautifully developed, dynamically variable surface of reflection as a tool. The choreographers selected the five dancers to ensure there are marked, detectable differences between them. The five characters are three men and two women who use their bodies together very seldom, even in the pas de deux. They express themselves outwardly as if they had no shared history at all. And what the first moment after Sad Case is about is entirely unpredictable.

Anna Braun

Trois Gnossiennes

This emblematic piece of the vast van Manen repertoire was premiered by the Dutch National Ballet (HET) in 1982. The two-cast ballet is the third piece of the five-part Pianovariaties (Piano Variations) cycle, created for the company between 1980 and 1984, and is followed by Sarcasm, the Budapest premiere of which was held in 1998. Interestingly, half a year before the world premiere of this work, Manen had already used Erik Satie’s eponymous composition alongside works by other composers in his piece Five Short Stories, which was not part of any cycles. The choreographer composed the female figure of the duet for ballet dancer Mária Aradi, whose exceptional career began at the Hungarian State Opera. The dancer lived in the Netherlands from 1972: she was principal soloist and later ballet mistress with the HET for more than three decades.

Based upon Erik Satie’s magically beautiful masterpiece, Trois Gnossiennes presents a picture of an unusual relationship. In this double portrait painted with sensible strokes of the brush, images of trust, sub- and superordination, relativity and interdependence flash one after another. Changing the lyrical and grotesque elements in a masterly way and linking the memorable features, van Manen presents monologues, dialogues and symbolic moments of a relationship that is abundant in intimate depth. The brilliant elevation of simple poses to acrobatic levels and the enigmatic and extraordinary play with the relaxed and then reviving bodies make this rich and brief ballet unforgettable.

Tamás Halász

Whirling

“At the moment, I am more interested in pieces without storylines. However, just because it does not have a storyline, it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have anything to say. If a motion or the aesthetics of a dancer causes the viewer to feel something, I think that is immediately connected to a kind of experience, which means it is filled with meaning for the viewer, which leads to the creation of a small story. Instead of specifics, I try to express an emotion,” claimed choreographer András Lukács. The one-act piece Whirling is in fact the expanded version of a pas de deux created years earlier which had been inspired by a scene from a film and its music composed by Philip Glass to which the iconic scenes are set.

The excerpt to inspire the choreographer can be seen at the end of The Hours, directed by Stephen Daldry based on Michael Cunningham’s novel. In the scene, Virginia Woolf slowly bids farewell to her life, her sickness, and all her physical pain as she walks into the river and submerges without even a glimmer of hesitation. The music is beautifully suggestive in expressing the river’s eddies and the woman’s fight to choose between life and death. The choreography set to the second movement of Tirol Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, also by Glass, makes the fight practically tangible, breathable: the filtered, cold light, the watery effects of the costumes, and the spiralling, circular motions are the exceptional artistic manifestations of the circle of life and death.

Márk Gara

Études

Études is a one-act ballet which poses a great challenge to ballet companies because its subject is the technique of classical ballet itself: the school, the everyday training and the assessment of understanding and skill. Perhaps this is why the famous American dance critic Arlene Croce dubbed this work an “anti-ballet”. Because, in a ballet, the perfection of skill in dance is traditionally presented to the audience through the content, and the arduous everyday practise usually remains hidden from the viewers. The dancer’s everyday work takes place in the ballet studio, where the “vocabulary” of dance is formulated inside each dancer’s body, which will later become the base for the performance of choreographies on the stage. The audience sees only the outcome.

Danish choreographer Harald Lander, however, decided to initiate the viewer by presenting on the stage how a ballet exercise is constructed, and how the pure beauty of classical movements and steps triumph over even the laws of physics. Because this ballet work is really the triumph of form, the presentation of ballet technique that proclaims its own beauty while remaining detached from plot or content. However, it is not a work of art devoid of content, as its subject is BALLET itself, in capital letters. It is a bold venture for both the choreographer and the dancers performing it because it requires perfection and holds up a mirror to flawless dance technique. This makes it similar to practice sessions in the ballet studio, where the customary mirror shows the dancer the results of his or her own work.

Ballet dancers all over the world begin their working days beside the ballet studio’s barre so as to perfect and maintain their bodies and their dance skills. Lander and Riisager chose the music of the Austrian piano virtuoso Carl Czerny because the juxtaposition of ballet exercise alongside piano exercises shows how practice leads to proficiency in both music and dance. As dance history legend has it, the composer Riisager was walking down the street when he overheard a child practising the piano through an open window. He was playing Czerny’s etudes. Standing outside the window, Riisager realised the uses of Czerny’s etudes for dance, and the idea came to him right there: ballet exercises should be brought to the stage to show the audience something that they normally cannot see.

Études is constructed as a ballet lesson: it begins at the barre, and then, through the increasingly complex exercises, it reaches its zenith, incorporating jumps and turns, and finally the stage combinations. This also gives us an impression of the structural coherence of classical ballet technique. And it comes from the choreographer’s assortment of ideas regarding how it was staged, with what kinds of lights, colours and forms, eventually showing the difference between work in the ballet studio and the premiere on stage. It is an excellent theatrical concept to play with contrasts, silhouettes, spatial forms, black-and-white colouring and lighting, which make the seemingly simple exercises faster and more exciting while directing the viewers’ attention sometimes to the legs and other times to the arms, or to the bodies stretching their muscles or the ports de bras. In the other parts of the work, the costumes and movements evoke the great eras of dance (Romanticism, Classicism, Neo-Classicism) in order to depict the developments in technique. From the ballet studio, we step out to the rehearsal room for stage practice, where, following the hierarchy within the company, the soloists and the corps de ballet demonstrate their skill. (After the 1948 world premiere, the choreographer taught the work to the dancers of the Opéra de Paris in 1951/52, modifying it slightly from a technical point of view and making it more difficult.)

In Lander’s work, the person of the ballerina is given special emphasis. The ballerina – the star of every company – was the central figure in ballets through long centuries of dance history. Lander evokes the figure of the ballerina of Romanticism by showing the legendary character of the Sylphide on the stage. In this part, which is inventive from a choreographic perspective as well, he uses the tools of the so-called “mirror-ballets” of the 18th and 19th centuries to “hold a mirror up” to both history and the internal world of ballet simultaneously, with the mirror accompanying the dancer through her career. Lander, who was himself fond of character dances, did not forget this important device of 19th-century ballets. He wove the motifs of the popular mazurka and tarantella into the classical variations with extraordinary elegance. The ballet concludes with a crescendo of both music and dance, in which the defile, or “procession”, of the entire company crowns the triumphal march of the classical ballet. “Études means a lot to me because it is a metaphor of my thoughts on ballet and dance. Dancing does not simply mean presenting a few steps to the audience. The purpose of ballet is much more important than that: it should unify spirit, dance and music!” – claimed Harald Lander.

Rita Major