The Goose of Cairo, or The Deluded Bridegroom

Details

In Brief

After the success of Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Mozart set himself to composing two new operas, but gave up on both of them. In terms of style. We can regard the two fragmentary comedies L'oca del Cairo and Lo sposo deluso as precursors to Figaro and Così, and at times even the world of Don Giovanni is discernable. The completed parts were never staged in Mozart's lifetime, but since his death, however, several successful pasticcios, meaning performances sewn together from excerpts from multiple musical works, have been made. An idea cherished by general director Szilveszter Ókovács for 25 years: to present Mozart's thus-far unknown opera, under the baton of Pál Németh and in a production directed by Attila Toronykőy.

Parental guidance

Events

Premiere: April 14, 2019

Synopsis

Act 1

In the castle of Ripaseccha, the no-longer-youthful and miserly marquis Don Pippo is preparing for his wedding, to the great amusement of his secretary, Calandrino. Don Pippo’s ward, Celidora demands that her guardian keep his promise by finally giving her away in marriage to the young man she loves, Biondello, who has been hanging around the house of the marquis for a year now. Don Pippo tells her that they will be celebrating a double wedding that evening. It won’t be Biondello that Celidora is marrying, however, because Don Pippo is giving her to a wealthy Roman count of similar age whose own ward he himself, it so happens, is preparing to marry.

Biondello looks woefully at the marquis, who laughs at the boy and dismisses him: the impoverished lad can have Celidora when the singing of the goose of Cairo makes dollars rain down from the sky. Calandrino racks his brains to figure out how he can help Biondello get his beloved back, but Don Pippo locks the girl in the castle’s tower in order to prevent any trickery.

The marquis happily welcomes the Roman guests as they arrive in the house: they are his veiled bride and his future father-in-law/son-in-law, the noble-spirited and sophisticated Lionetto. As Don Pippo accompanies the count to the castle tower to introduce him to his future wife, Celidora, Calandrino is forced to entertain Don Pippo’s bride. The woman removes her veil, and the secretary is astonished to behold Lavina, his beloved. He immediately resolves to spirit her away. When Don Pippo returns to find the two lovers in each other’s arms, he has Lavina locked in the tower together with Celidora and entrusts the key to Auretta, the chambermaid.

Calandrino woos the tower key out of Auretta’s hands, a scene that is nevertheless witnessed by Chichibio, the stable-boy… who is also Auretta’s lover. He immediately grows jealous.

The “big meeting” between Count Lionetto and Celidora takes place: it turns out that Don Pippo has sent the love letters that Celidora wrote to Biondello to Lionetto, who for some reason addresses the girl as “Clarice”. Celidora bitterly announces that the old man will only be her husband when the singing of the goose of Cairo makes dollars rain down from the sky.

Act 2

After his afternoon nap, Don Pippo feverishly instructs Auretta and Chichibio to prepare everything for the double wedding. The chambermaid and the stable-boy, however, decide that the lovers should be together and resolve to help the youngsters avoid the forced marriages.

In great secrecy, Calandrino brings the girls down from the tower. Celidora and Biondello fall into each other’s arms, and the lad produces money to help his lover out of her trouble. Lionetto surprises them and, left alone with Celidora, objects that she is not the same person as Clarice, whom her “father” said so many good things about, as she was neither learned nor even virtuous. Celidora bitterly explains to Lionetto that she has always been in love with someone else and that her guardian has a heart of stone. Finally, she tosses the money in front of the older man and hurries off. After some moments of thought, Lionetto addresses Chichibio, who is right then stealing around the area in a goose costume, and tells him to inform his master that the two lovers are getting ready to abscond right now. He himself decides to put an end to the drama; he gathers up the money from the floor, along with the goose costume that the stable-boy has left there, and hurries off.

The four lovers are prevented from fleeing by the river in front of the castle, so they summon workers to quickly build a bridge over the water. The work is feverishly being carried out when Auretta and Chichibio bring news: Don Pippo is approaching!

The marquis indeed arrives, and in a terrible rage is about to throw the entire company in prison right away. Suddenly, however, Count Lionetto appears from the tower dressed as a goose and tossing gold dollars to the ground. He attempts to appeal to Don Pippo’s better nature: “Now I can see that, on this earth, everyone should only marry for love. Two old ganders caused this fuss, and now this famous specimen will bring peace: I myself am the ‘goose of Cairo’, and I myself am the ‘deluded bridegroom’!”

Media

Reviews

Opera guide

Introduction

Pasticcio, or pastiche – that operatic pie assembled from various works – was a favored genre of the 17th and 18th centuries, and even Rossini’s music was cobbled into such compilations. Later, operettas tended to flourish in this fashion: think only of Wiener Blut (Viennese Blood) or Das Dreimäderlhaus (Blossom Time), both stitched together from the music of Johann Strauss the Younger. In our own time, however, the operatic world has rediscovered this method (must we explicitly invoke postmodernity here?), and so new posthumous hybrids and chimeras have been born, some of which have proved remarkably viable. Thus, a few years ago, two unfinished Mozart fragments – both begun around 1783–84 and left incomplete – were combined on our stage: L’oca del Cairo (The Goose of Cairo) and Lo sposo deluso (The Deluded Bridegroom).

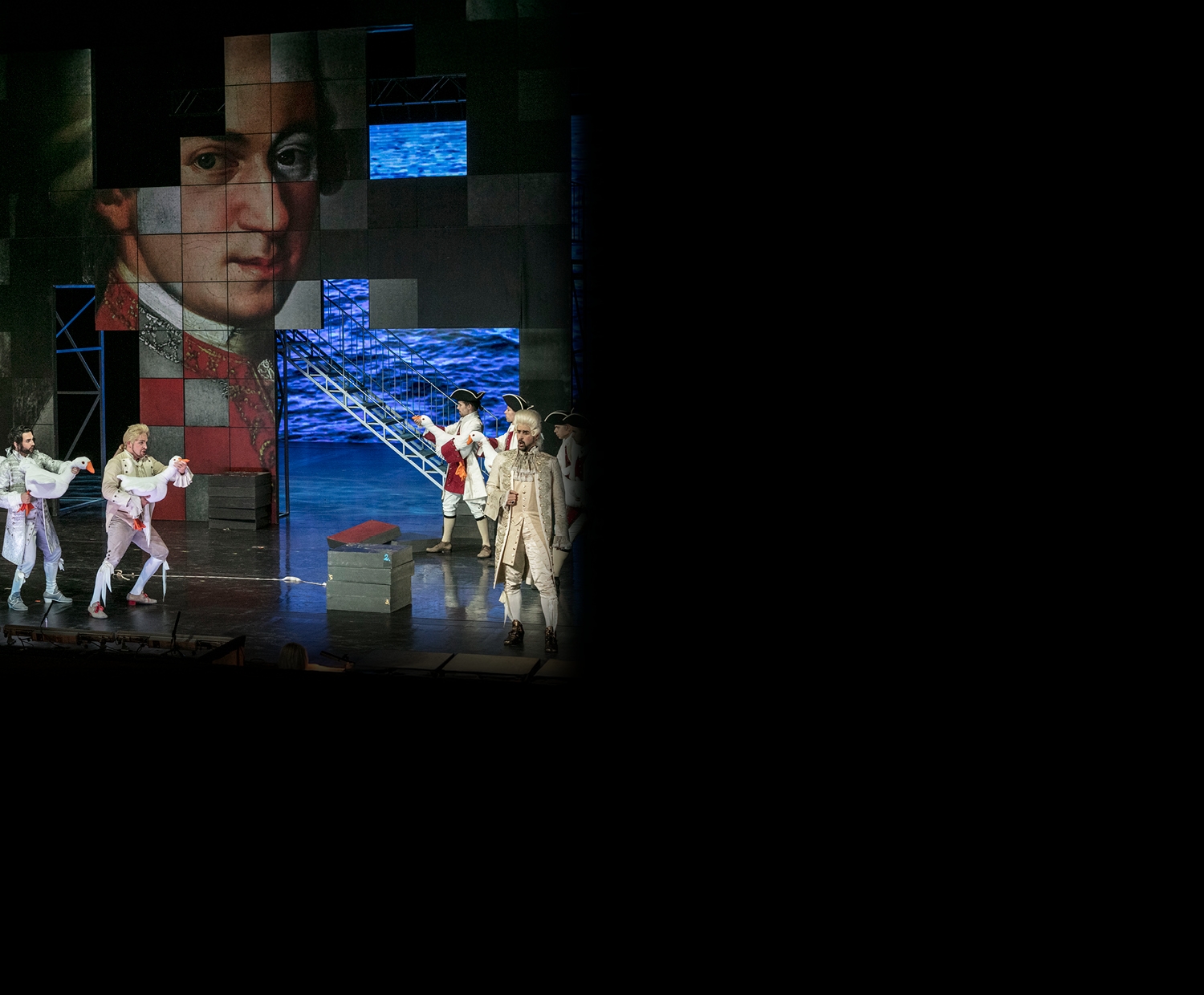

The chief merit of this crossbreeding, the work of Pál Németh, which resulted in L’oca del Cairo, ossia Lo sposo deluso, is of course that it rescues Mozart’s music for the operatic stage, drawing on the scraps from the workshop of a composer who by then had embarked on his independent Viennese career, already mature and accomplished. For Mozart we are curious, receptive, even hungry in every respect (he too deserves the phrase “every inch a king”), though we know well that the sudden discovery – or cloning – of another Figaro or Don Giovanni is out of the question. Yet it is still a genuine delight to toy with lesser-known Mozart pieces, and it was precisely this playful, caricatured opera buffa spirit that dominated the new pasticcio’s 2019 premiere. Attila Toronykőy’s staging concentrated wholly on playfulness, just as Katalin Juhász’s design concept did, its most essential and versatile elements being, most fittingly, a set of oversized mosaic blocks.

Ferenc László

The idea

These two unfinished works by Mozart have only been recorded a few times – and only separately. There are even fewer productions that tried to adapt them to the stage – again, only separately. The idea of a possible organically connected stage version, however, had already been forming in my mind in the 1990s. The idea came from a recording. In 1991, Phillips released the complete works of Mozart to commemorate the bicentenary of the composer’s death. Among the many discs, a solo-CD was also released with the two fragments, conducted by Peter Schreier and Sir Colin Davis. If my role model at the time, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, had not sung in it, I may not have even noticed it. I was listening to the music of the two fragments and reading the text of unfinished librettos in the guidebook, as well as the excellent treatise of Erik Smith, which included relevant quotes from the letters that Mozart wrote his father during the composing of the two works, and I was amazed!

Before composing Der Schauspieldirektor and Le nozze di Figaro, Mozart was working on these two fledgling operas, the plots of which are concerned with the abduction story that was so popular at the time – just like his previous work, the Singspiel entitled Die Entführung aus dem Serail or another entitled Zaide. Through the years, diving deeper into Mozart’s oeuvre, listening to the disc over and over, I realised that this genius artist integrated many musical innovations into these two fragmented pieces that could not be found in any of his previous works, and sometimes not even his later works. The fantastic overture of Lo sposo deluso, for instance, lacks cadence, transitioning directly into a quartet – Mozart had already done something similar in Il re pastore, but this two-part overture has such a beautiful and slow flute theme, it may even be one of the most beautiful of all of Mozart’s works – and it is unplayable at concerts because of this lack of cadence, and so nobody knows about it today.

Another interesting example is Auretta’s “Se fosse qui nascoso” aria from L'oca del Cario, which is concluded by another character, and with a recitativo, that's all! Who has seen such a thing? Also in L'oca del Cairo, Don Pippo’s aria becomes a trio all of a sudden. Only the entrance of Elvira in Don Giovanni is comparable. Furthermore, Mozart’s shortest aria is also found in L'oca del Cairo, which is even shorter than Don Giovanni’s Champagne Aria. Chichibio gets the whole song over with in less than fifty seconds. Or see the tenor aria from Lo sposo deluso, which ends with a sudden and baffling change of musical character. There is even mention of a Hungarian city in L'oca del Cairo, apropos the wigs from Esztergom; that is unique as well. Mozart’s only visit to Hungary was to Bratislava, where he would have been welcomed by a patronage of Hungarian nobles. Even though his first opera, La finta semplice includes two Hungarian characters, captain Fracasso and baroness Rosina, he has no other direct stage connection to Hungary.

L'oca del Cairo and Lo sposo deluso are full of ground-breaking ideas, which are already apparent here but will only reach their full potential in Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni. As the plots of the two fragments can be paired together and the voice types of the characters match, it is only fitting that the existing fragments of the two works should be combined to show the audience these wonderful pieces of music that have been hiding in Mozart’s drawer.

I sought out Pál Németh with the idea, who is an expert in early music, and with whom I had worked much around that time. He brushed me off at first, but later he became intrigued with the idea – even though ten years have passed in the meantime – and we dove into the work head-first. I tried to find the bumps and holes in the connected fragments, and we fixed them together. For instance, with Mozart, it was impossible for some characters not to have their own arias, so we had to borrow a few from other works for a couple of them. We tried to find concert arias that originated from the time the two works were composed and had lyrics that fit the context. This is how the famous “Un moto di gioia” aria came to be included in the performance, which was originally an alternative aria for Susanna in the second act of a 1789 revision of Le nozze di Figaro, and which we gave to Celidora. We changed the silent character of Biondello to a singing one. We improved a couple of recitativo seccos, in order for the story to flow more smoothly. After all, even Mozart had left all the seccos of La clemenza di Tito to Süssmayr!

After years and years of waiting, we finally set the date of the premiere in the OPERA, and we commissioned Attila Toronykőy to direct it, who was already familiar with one half of the production, L'oca del Cairo, which he already worked with in a directing exam at the University of Szeged. We chose him because of his great imagination and sense of humour, to bring this story full of surprisingly absurd moments to stage. Attila’s excellent sense of dramaturgy has also produced more than a few useful and logical observations and ideas that have further enriched the work. We are delighted to inaugurate both our work and the Bánffy Stage of the Eiffel Art Studios with a true experiment, in the hopes of producing the “sixth full opera of Mozart”; the most important quality of which is that it makes presentable two works that have been hitherto unfit for stage, yet are more precious than gold.

Szilveszter Ókovács

The conductor’s thoughts

When Mozart decided to compose a comic opera in Italian, he read nearly a hundred librettos, but he didn’t like any of them. He agreed to work with Varesco, for lack of a better alternative, but their cooperation could hardly be called smooth. Mozart stopped working on it because he wasn’t satisfied with the story, nor with the text. He was waiting for the “big game”, Lorenzo Da Ponte, who was working with Antonio Salieri at the time. Their great partnership began when Da Ponte became available. More than one study claims that the text of Lo sposo deluso was written by De Ponte, although not originally for Mozart.

Szilveszter Ókovács was the mastermind behind developing the plot and curating the text. I tied the existing numbers together and completed the incomplete ones. The overture, some other parts, and the libretto of Lo sposo deluso have survived in their entirety, so it seemed obvious that it should make up the first part of the work. Only L'oca del Cairo was written a true finale, coincidentally, so that became the conclusion. Where something was missing, we inserted a couple Mozart-arias; the arietta written for Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro, for instance, which is never performed otherwise, despite its excellence. Our goal was to allow the completed parts of Mozart’s composition to shine, while using them as guidance in restoring the rest.

However, there were some numbers that only had vocals and an orchestral bassline or just the first few beats, and we had to imagine the kind of orchestral accompaniment that the composer had envisioned. Of the many recitativos in our pasticcio, only two were composed by Mozart; the rest only exist in text form, so we had to create music for them: I lifted the music for most of them from other works of Mozart, and the rest I composed myself. We had to research a lot of details in order to create a coherent whole. For instance, I looked into the types of parts Mozart wrote for different instruments in the first half of the 1780s, the time when he was working on L'oca del Cairo and Lo sposo deluso, and I expanded the orchestral accompaniment accordingly. Working on this was what exploring Africa must have felt like: the whole “map” was blank at first, ready to be drawn upon during the expeditions – with musical notes.

Our goal is to present a complete story, through which we can show the audience all this wonderful music that would otherwise only languish on a sheet, unperformed. There is a metaphor I like to use: the chips falling off the workbench of the goldsmith are also gold. Similarly, every note written down by Mozart is beautiful in itself. Even the smallest tune he scribbled onto a napkin while sipping champagne is perfect. Just like Lo sposo deluso and L'oca del Cairo. Our duty, or our mission, even, is to find these music sheets at the bottom of the drawer, take them out and give them voice, to make these rarely, if ever, heard melodies audible.

Pál Németh

About the two unfinished Mozart operas

In the four years after the composition of Die Entführung aus dem Serail in 1782, Mozart was flirting with the comic opera genre. “I have looked through a hundred libretti, and more, but have not been able to find even one with which I am satisfied” – he wrote to his father in Salzburg. “The chief thing is the comic element – I know the taste of the Viennese” – wrote Mozart to one of his potential librettists, while still looking for a new libretto for his latest opera. The fruit of this labour was L’oca del Cairo (The Goose of Cairo), an abortive project if there ever was one. It is perhaps a measure of Mozart’s desperation that he should not only be prepared to consider collaborating on a comic opera with Abbate Varesco, the librettist of the opera Idomeneo, who, as he admitted, had “not the slightest knowledge or experience of the theatre” but should actually work on so barren a tale off and on for six months before finally acknowledging that it was hopeless. The story of an old Marquis who betroths her daughter to a man she doesn’t like, and keeps her shut up in a tower from which the daughter’s true love can rescue her with the help of a giant mechanical goose, certainly won’t join the pantheon of drama.

In a letter written after his return to Vienna, Mozart mentioned that he and Varesco discussed the opera in person. Varesco set to work at once and provided him with a draft of the libretto of the first act. Some of the eight numbers which survive, mostly in sketch form and all from Act 1, were written in Salzburg, and some on the journey back home. The finale was sketched in Vienna in December. By then, he was having serious doubts about the mechanical goose: “My only reason for not objecting to this whole business”, he told his father, “was that two people of greater penetration and judgement than I had no objection to it – that is, yourself and Varesco.”

This, though surely meant ironically, is a lame excuse. Mozart should have realised much sooner that the Abbate was out of his depth and incapable of creating a comedy with characters and situations that are even remotely realistic. Later, when he found that Varesco has written, in the margin of Act 2, “the music of the preceding cavatina will do for this”, Mozart finally lost his temper. “That is out of the question. In Celidora’s cavatina the words are disconsolate and depressing, whereas in Lavina’s they are comforting and full of hope. Besides, for one singer to echo the song of another is completely out of date. [...] Further, the audience would hardly be able to tolerate the same aria from the second singer, having already heard it sung by the first.”

Still, Mozart soldiers on – the letter is full constructive criticism for improving the libretto. However, the next letter reveals that L'oca del Cairo has been put on one side. Mozart had to focus on other works to bring in money faster. By this time the Goose was well and truly cooked, and nothing further was heard from it. Another opera fragment, Lo sposo deluso (The Deluded Bridegroom) probably dates from about the same time. It may be the libretto Mozart mentioned in a letter: “An Italian poet” brought him a text, which “I shall perhaps adopt if he agrees to adjust and tailor it to my liking” – he wrote. The poet is often assumed to be Da Ponte himself.

Though neither of these attempts got anywhere, it was not all wasted effort. Writing the ensembles – L'oca del Cairo’s finale especially – provided Mozart with useful experience towards acquiring the mastery of the contemporary style of opera buffa, infused with his own inimitably personal voice. The true importance of L'oca del Cairo – which is composed of only a few arias, two duets, a quartet, and a finale – for Mozart’s dramaturgy is that it was his first true, eventful buffo finale: through-composed and with two opposing groups, in which the roles are delineated further through distinct musical characterisation. This was the prelude to Mozart’s great Da Ponte-operas: Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così fan tutte.

Judit Kenesey

(Based on Mozart on the Stage by János Liebner and Mozart and His Operas by David Cairns)