Bittersweet Comedies

Walking Mad, Cacti, 5 Tangos

Details

In Brief

Dance and self-reflection. The classical seen through the modern. Lightness and gravity. These might be the words to describe the three ballets presented in a single evening. Bittersweet Comedies brings together the dance works Walking Mad, Cacti, and 5 Tangos. “I came up with the idea of a wall that could transform the space during this minimalistic music and create small pockets of space and situations. Walking Mad is a journey in which we encounter our fears, our longings and the lightness of being,” explains Swedish choreographer Johan Inger about his piece. At the center of Cacti stands the language of dance itself: a (self-)critical caricature – ironically enough! – expressed in the very language of dance. In 5 Tangos, opposites dissolve: contemporary and classical styles intertwine and merge.

Parental guidance

Events

Premiere: May 17, 2001

Walking Mad

Johan Inger, former artistic director of the Cullberg Ballet and a former dancer with the Royal Swedish Ballet and Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT), made his debut as a choreographer nearly a quarter of a century ago at the encouragement of the highly influential Jiří Kylián. His first attempt (Mellantid) was immediately crowned with success, followed by numerous further choreographies, including Walking Mad, created in 2001 for nine dancers to Ravel’s Bolero. The work is based on the Socratic observation: "our biggest blessings come to us by way of madness". "The famous Bolero from Ravel with its sexual, almost kitschy history was the trigger point to make my own version. I quickly decided that it was going to be about relationships in different forms and circumstances. I came up with the idea of a wall that could transform the space during this minimalistic music and create small pockets of space and situations. Walking Mad is a journey in which we encounter our fears, our longings and the lightness of being," said the choreographer.

Cacti

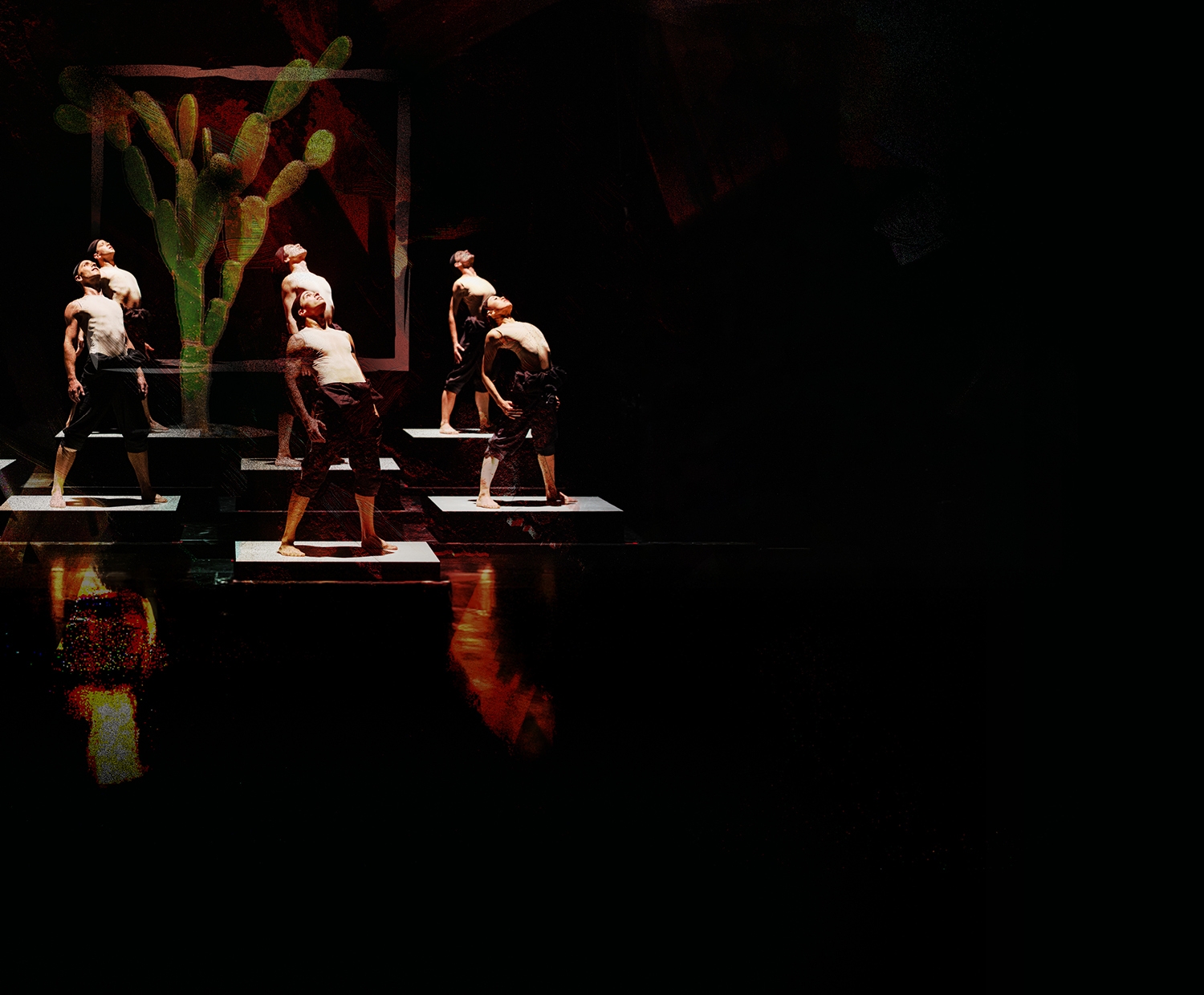

Choreographer Alexander Ekman addresses on the contemporary dance stage a theme with which he defines himself as well: modern dance itself. The work passionately, and often raucously, picks apart the mannerisms of dance. Sixteen dancers stand visibly frozen on gigantic Scrabble tiles. While the string quartet plays and ironic-sounding words are heard spoken, the dancers run around, fall down, writhe on the floor and attempt to escape from their invisible prison. Eventually, each of them acquires a cactus. A play of rhythms between dancers and musicians.

5 Tangos

5 Tangos is one of Hans van Manen’s best known and, deservedly, most popular works: superb music and dance combine to evoke a pulsing metropolis and a world of fiery and passionate instincts. Sometimes sultrily lethargic and other times set to accelerating tempos featuring virtuoso elements, this thrilling work plays with solo and group scenes to reveal the changing games of the individual and the community, the many faces and layers of love and attraction and a portrait of an era.

Media

Ballet guide

Walking Mad

This dance performance with a captivating mood, minimalist spectacle and powerful contemporary movement vocabulary was originally made for the dancers of the Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT 1) in 2001 and has won many major awards. Maurice Ravel’s well-known Bolero inspired the choreographer, but he regarded this very familiar, frequently adapted piece as only a starting point. “Walking Mad is a journey in which we encounter our fears, our longings and the lightness of being”, Inger explains. However, the journey, to which the opening image of a man arriving in a hat and coat unmistakably refers, also explores the absurdities of daily life, naturally in the context of the timeless subject of the relationships between men and women. As the thoughts of the piece do not follow a single strand throughout, the choreographer likewise finds unexpected ways to use the music.

It may seem crazy that the well-respected piece of music is abruptly interrupted, falls silent, and then a short while later starts again. As such, it is precisely the sweep of the music that the choreographer cuts. Then, finally, the last chord of the dance work is not Ravel’s usual climax, but a work in stark contrast, Arvo Pärt’s poetic piano piece Für Alina (1976), which sets the background of the parting duet about separation and letting go. The main creative prop on stage is a moveable plank wall rolling on wheels, which expands the movement options: it can be climbed on, hung from, slammed into; doors open and shut in it, but it can also fall, only to lift the dancers’ bodies up when it rises again. It can be danced on and against... It is the symbol of the limits, opportunities, barriers and gateways of our lives...

Rita Major

Cacti

Cacti was created in 2010 for the young artists of the Netherlands Dance Theatre and was inspired by a decidedly unpleasant series of events. Its topic is the asymmetrical and strife-ridden relationship between artists and critics. Alexander Ekman thinks back to the period of his life when he wrote the work: “It was created during a period of my life where I was very upset every time someone would write about my work. I did not find it fair that one person was going to sit there and sort of decide for everyone what the work was about. I believe that there is no right way and that everyone can interpret and experience art the way they want. Perhaps it’s just a feeling that you can’t explain or perhaps it’s very obvious what the message is.”

Can we, as viewers, accept that there is not always a need for analysis, that enjoying art can simply be an intuitive, emotional process and nothing more? Or do we always need someone to explain to us what it is we are seeing? Cacti shows us a criticism of our world, built upon our self-importance, in a language that is exact and unforgiving, yet still full of love. For Ekman, this piece proved to be his professional breakthrough: the work has been on the repertoires of more than 15 companies across the world. “Cacti is definitely one of those works for which I will always feel a certain love. It is extremely hard to create a piece which feels complete and finished from beginning to end. I think with Cacti we somehow managed to arrange the pieces of the puzzle in a way so that the curve feels complete.” It was nominated for the Dutch Zwaan dance award in 2010, the British National Dance Award in 2012, and the celebrated Olivier Award in 2013. The Hungarian National Ballet first performed the work in 2020.

Anna Braun

5 tangó

5 Tangos is one of Hans van Manen’s best known and, deservedly, most popular works: superb music and dance combine to evoke a pulsing metropolis and a world of fiery and passionate instincts. Sometimes sultrily lethargic and other times set to accelerating tempos featuring virtuoso elements, this thrilling work plays with solo and group scenes to reveal the changing games of the individual and the community, the many faces and layers of love and attraction and a portrait of an era.

Anna Braun